Hugh Miller Inlet

Timeseries of one of the plots (for which monitoring continues)

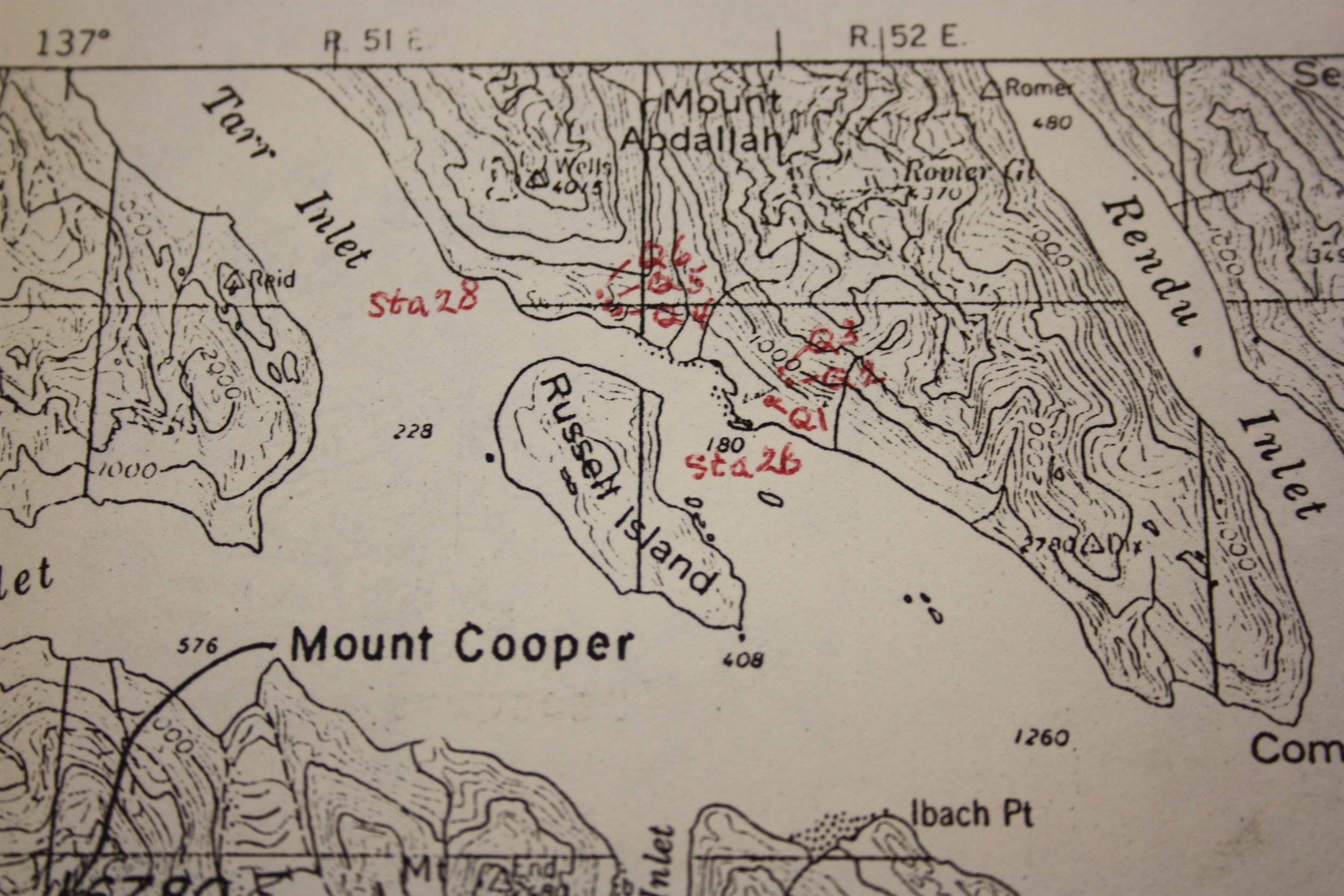

1944 map with approximate plot locations

Notebook: Map built from 1916 descriptions, with paces and compass bearings indicated

Cooper’s original 1916 field notebook, courtesy University of Minnesota

Allison Bidlack working towards one of the plots

Blue Mouse Cove

Glacier Bay, Alaska, is fresh wilderness - almost unique in the world. Only 150 years ago it was covered in ice hundreds of meters thick - full to the brim, with only the ringing mountain tops exposed to the winds. Then the sheet collapsed, catastrophically, exposing fresh rock and gravel.

Since then, a vast wilderness has grown up, untouched by people. While tourists can make it into the mouth of the bay on boats, the back of the bay, and the forests ringing it, are essentially untouched. It is one place where almost every footstep is new. Bears and wolves abound, many having never seen a human. I’ve been within 3 feet of a full grown coastal brown bear who was simply curious, wondering what oddly clad animal he was seeing. That bear was so intrigued it lay down, and we stared at each other for five minutes. That story is here: https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/bear

But the unique contribution of Glacier Bay to exploration and science is what one scientist started in 1916. Following John Muir, William Skinner Cooper established 9 plots on the glacial till, bare plots only a few meters from the walls of ice. He then returned, occasionally, and then one of his students, until that student died in the early 1990’s. The plot locations were lost with him.

But in 2016, with funding from National Geographic, I found old directions from Cooper’s original notes (from 1916). The directions were vague - paces, compass bearings, sketch maps. Everything had changed. The shoreline had risen up, freed from the ice, and looked nothing like the lines he drew. Magnetic north shifted (as it does), meaning the bearings were off. And Cooper measured in paces. His plot markers were buried with soil now. It was scientific exploration crossed with Indiana Jones and a dash of Treasure Island. But we were ultimately successful, despite rain, wind, bears, and kayaking rough seas.

The site is now the longest running permanent study in the world, where we can follow ecosystem development in ways that have never before been done for this amount of time. The data is invaluable. It was featured as the cover story in Ecology, the flagship publication of the Ecological Society of America. We have already learned an immense amount, and will continue to learn more as we follow these plots.

The next revisit is planned for 2024.

People

Brian Buma

Sarah Bisbing

John Krapek

Glenn Wright

Allison Bidlack

Greg Wiles

Chris Fastie

Lewis Sharman

Selected Content

Here and Now (NPR / WBUR Boston): Climate scientist finds buried treasure in Alaska glacier. Radio special.

Century long glacier study may help us crack climate change. 2017. National Geographic.

Buma B, Bisbing S, Krapek J, Wright G. 2017. A foundation of ecology re-discovered: 100 years of succession on the William S Cooper permanent plots shows importance of contingency in community development. Ecology. 98(6): 1513-1523.

Buma B, Bisbing S, Wiles G, Bidlack A. 2019. 100 yr of primary succession highlights stochasticity and competition driving community establishment and stability. Ecology. 100(12): e02885

National Park Service project report (materials are also at the park and distributed to tourists about this work)